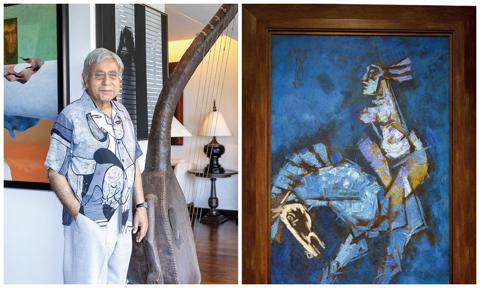

One is indeed privileged to be invited into the effervescent, ever-youthful world of pharma-icon Ajit Singh. There’s a celestial sense about his home. Spanish guitar music soothes away any mental noise. There’s that ‘Lost Horizon found’ feeling in the expansive swathe of sea and sky, just beyond his terrace garden. Walk up towards the sea, and you spot the delicate ballet of the waves, that eternal, cosmic dance. Like the mythical Shalimar, time cannot be felt here.

The soul of his paradise, Ajit Singh’s presence is unobtrusive in his own home. Everything happens in silence — guests are served their coffee, staff mishaps don’t provoke a raised voice. What moves one deeply is when he tells his guests, “You know employers in India generally pay modest wages to our household help, and from that, they raise a family, send kids to school, pay for medicines and rent, buy their white goods and look after their parents. And we treat them as though they don’t have the capacity to think! Instead of telling them to ‘do this’ or ‘do that’, I believe it’s smarter to ask, ‘How would you like to do this?’”

When the success of a corporate family is reaped slowly, intelligently, sensitively, the home and office spaces are also, by default, richly defined by art, each work pregnant with its own story. Strung together, you have a symphony of such stories.

As we walk around the spaces and listen to the tales in the colours and cadences all around, we are transported. “My art collection has two aspects — one part consists of works by well-known artists; the other comprises works I conceived and got young artists to execute.”

But what one finds truly revelatory is not this pragmatic categorisation, but what both parts of his collection eventually reveal about their owner.

“My family has over 450 paintings, collected over a long period of time, since the early 70s. At that time, contemporary art and artists were mostly ignored. We had a few art patrons, Parsis like Homi Bhaba, the Taj group of hotels, the Tatas. India was in the throes of economic struggle and socialism. So in that climate, art was treated as a ‘side interest’, so to speak. Just like chefs were in those days. But chefs today are sometimes paid higher than the managing director of a hotel!” he observes, a twinkle in his eye.

Ajit and his brother Jasjit Singh returned to India after studying at Cambridge, Harvard and London universities, where they had seen the “treasured position of art” in the homes and offices of friends in Europe — only to find that in India, a land famed for its rich artistic mien, art was nowhere!

“We saw how art enlightened an environment, and we thought we must do our bit to encourage the growth of contemporary Indian art and artists. We didn’t have much surplus funds then, but paintings were so ridiculously inexpensive that we were able to start collecting art without feeling any strain on our pockets!”

Discovering an iconic artist — on the floor of a chemist’s store!

Ajit had a serendipitous relationship with MF Husain’s early works. “Yes, we have over a dozen Husains, largely collected in the 70s. One of the ‘retail’ outlets for these was the Geeta Chemist shop, near the entrance to the Oberoi Hotel in Delhi. Husains on the floor were going for Rs 1,800 to Rs 2,000, priced depending on the size rather than on the complexity of the work! So all I had to do was take out whatever money was in my pocket, choose a Husain, roll it up and then bring it back to Mumbai,” he recalls with a smile.

Later on, his sister-in-law, Kavita Singh, an accomplished interior designer, copiously added to the collection, buying very significant works. “We have tried to pick up the ones in which we could see a lot of meaning, or an implicit business message not intended by the artist...”

Ajit then shows us another work: “We have another Husain, showing a man playing a tabla. If you look carefully at his right arm, he is surreptitiously holding a sten gun, ready to be used. But the music flowing out is soulful and beautiful. The message to me is: if you want to get done what you want to get done, do it with persuasive humility and sweetness; why use violence? Use the higher means. For me, personally, it’s very important to be pleasant and thoughtful with people.” We witness that in how much his staff adore him!

Selling soul vs selling out

Having known the Indian art scene at its most nascent, Ajit has seen artists at their most vulnerable. We have to remember that in the 70s, India was tattered economically by her colonial past and a nation just 20-something years old. With films like Roti Kapada Aur Makaan, where did art fit? So he grew to admire the courage of the artists in India, some even near his residence, many whose studios he visited to see them passionately at work, uncertain of their futures.

“In hindsight, I’ve observed that artists need to struggle with their circumstances. That’s when you feel that fire. It’s only once they’ve made it that we see an assembly line production of works…And they are then prisoners of their own success! These later works don’t radiate the same depth of perception or honesty to me.”

We then look at a rare Anjolie Ela Menon artwork, which has been in his possession for 30 odd years. The attractive girl in the picture is strangely a replica of his late wife, who the painter had not even met at that time.

“This soulful painting is an early example of a series where she adopted a Russian-influenced style. It has so many rich layers of symbolism. For example, you keep wondering what that dove is doing on the left, why that hand is reaching out from behind, who that girl is peering from behind... Is it the subject herself? Could there be two of her in there? Strange for a girl to be holding a goat... And then you see a mask with ears, indecipherable marks on the lower left side... that’s Anjolie’s message that there’s a mystery. This is probably her most magnificent work.”

Bikash Bhattacharjee: A work rendered in a trance

We walk towards a painting rooted in the birthing pains of a new country. We notice that a lot of artwork connected to nation-building, from the turbulent 70s, have dark, sombre tones. Ajit agrees — and cherishes this one masterpiece by Bikash Bhattacharjee, an extreme leftist from Calcutta. “He felt India was going to undergo a revolution. He was against the upper classes and their selfish accumulation of wealth. You notice all these Russian-like red flags in the raging crowd. You have this sense of anger, rebellion, darkness... Crowds of people running amok in the smoke emanating from buildings set on fire. It’s a scene showing burning and looting in the streets of Calcutta. And right on top, in the foreground, these ominous feet suspended with ropes around them. It’s open to interpretation whether they belong to a revolutionary who’s been hung in a public space or Kali, observing the anger and unrest,” he shares.

Bhattacharjee was so overcome when he made this work that “he told me he actually lost control. He didn’t paint as normal with a brush, but smeared the paint with his bare hands. And if you turn off the lights, you see the sunlight on the balustrades... it just leaps out!” Indeed, we turn off the lights and see the brilliant play of the sun’s reflection.

Ajit feels that Bhattacharjee’s finest works empathised with the bhadralok, the prevailing common people of West Bengal. It was their lost dreams, crippling superstitions, national hypocrisy and corruption that fired his visual narratives. “Later, he made portraits of society women for paltry sums of money and died in 2006 after that phase. I genuinely feel painters, if they don’t have a tragic life, are not creative. There’s neither depth nor passion; they then just churn out what the market seems to want.”

Mother India on a stretcher, pregnant, with potential

Next, we are shown a very powerful painting, again with deep black tonalities, dating back to the 80s. It’s a depiction of a pregnant woman dressed in fabric dotted with reds and yellows, sleeping on a peasant’s khatiya, with three hollow- eyed people who look lost, innocent, trusting and blinded, though with eyes open hovering around, with spooky, colourless flowers around the supine woman’s head.

“To me, this work says that the woman depicted is Mother India, sleeping. It’s a land where nothing much appears to have happened from time immemorial and yet, she’s pregnant with potential. This is a work from West Bengal again, and these simple bhadralok are around her. The pregnancy conveys that Mother India is going to give birth to something great in this century, but it could be a bloody pregnancy, not an easy birth... You don’t want to ever part with this phantasmagoric depiction of the future!”

We gaze for a long time and feel the energy of the work, both portentous and ominous. She rests on a rustic, basic khatiya, showing how a majority of India slept. “It’s about 43 years old, and I still find it very powerful...”

Photography: Ryan Martis

This story has been adapted for the website from a story that was originally published in HELLO! India’s June 2022 issue. Get your hands on the latest issue right here!

- Quick links

- Art

- MF Husain

- Paintings

- Ajit Singh